Katelyn Carpenter, PT, DPT & Jimmy Sliwa, PT, DPT, CMTPT

Most runners have probably heard they should change their running shoes every 300-500 miles. Perhaps good advice if you truly believe running on worn down shoes can lead to injury. When a runner begins to experience pain with running, shoes are usually the first thing to blame. Am I running in the right shoes? Are my shoes to old? Do my shoes support my high arches? The reality is, shoes are not the problem, they are just the easiest thing to modify. Unfortunately, the reality is that shoe companies want consumers to keep buying new shoes. In a study performed by the US army, it was shown that the type of running shoe is not indicative of injury prevention. The US army divided over 3,000 recruits into two groups; one that received a standard stability shoe while the other group had custom shoes based upon foot shape. The recruits were then taken through basic combat training and evaluated for injuries. The results of the study showed no difference in injury rate between the two groups; indicating that choosing shoes based upon foot type is useless.

For high mileage runners, changing shoes every 300 miles means buying new pair of shoes every month. This gets expensive and is unnecessary because shoes have the ability to recover just like all athletes! The material breakdown of shoes is greatest during the first 100 miles of running. After the first 100 miles, the change in initial shock absorption is minimal. A better practice to buying a new shoe every month, is to alternate between two pairs of shoes so that one gets a rest day. Shoes should be comfortable every time they are worn. So when clients ask their physical therapist, what kind of shoes they should wear when running, the proper response would be “wear whatever is comfortable.” If shoes are not the problem, what is?

Shoes are not the problem, instead tissue is the issue

Recurrent running injuries are a result of improper/overloading of tissue (tendon, muscle, ligament). Think about it; running is a very repetitive activity. If runners repeatedly overload body tissue incorrectly, then the body will certainly break down and develop pain. Shoes have very little to do with injury prevention. If running shoes offer very little protection against injury, what can a runner do to prevent running injuries? There are two primary predictors to avoid injury: 1) avoid training errors and 2) avoid biomechanical faults. The running industry force feeds a lot of misconceptions in regards to injury prevention and running. The best protection against running injuries is to optimize an appropriate training program and develop proper running form.

Avoid Training Error

Get this, 85% of all running injuries are a result of training errors. This is a staggering number that all runners need to pay more attention to. Common training errors include: progressing weekly mileage too quickly, without adequate rest between high intensity days, and not offering enough variability in the running routine. A good rule of thumb for novice and experienced runners is to avoid progressing weekly mileage more than 10% per week. For a novice runner putting in 15 miles a week, that means they should only add an additional mile and a half to the following week. Gradual progression is key to allowing body tissue to adapt to new training loads. Inadequate rest is another common training error. Athletes value high intensity effort because they push their bodies to new levels, but if they fail to give their body adequate rest then a state of tissue breakdown occurs. A good option is to limit high intensity running workouts to 2-3x per week with at least a day rest between sessions. Finally, not adding enough variability into a running program can lead to tissue breakdown. If runners always run on flat concrete terrain, consider running hills or trails or perhaps modify the running speed and cadence from time to time. The body is constantly adapting to the stressors we place on it; therefore adding variability helps avoid tissue overload.

Avoid Biomechanical Faults

Although running is one of the most basic forms of exercise, we should not treat it as a basic activity. Running properly requires strength, mobility, and skill. A lack or imbalance in one of these areas leads to faulty running mechanics and faulty mechanics can lead to injuries, which is one of the primary reasons that novice runners don’t stick to their program.

Strength

Most novice runners lack the strength to sustain a healthy running program. For people who are going from couch to 5k, it is likely they have not developed the three most important running muscles, gastrocnemius-soleus, hamstrings, and gluteus medius. The gastroc-soleus complex is the single most important muscle for propulsion, the hamstring is an important hip decelerator, and the gluteus medius is the most important stabilizer of the hip. Before beginning a running program, novice runners should strength train these individual muscles. Not only will it ward off injury, it will assist in performance as well. A good example of exercises for each are, eccentric heel raises, single-limb deadlift, and hip hike.

ECCENTRIC HEEL RAISES.

Lift up on two and slowly come down with one.

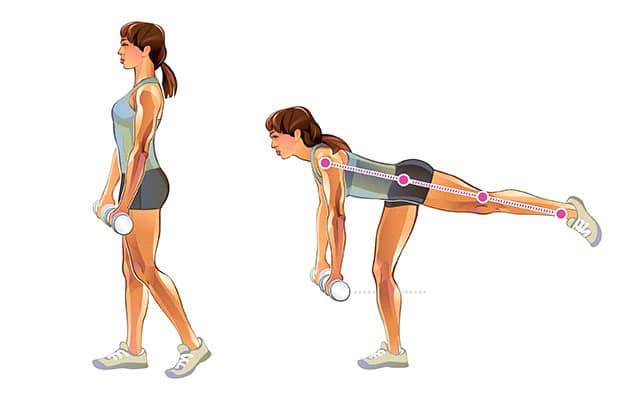

Single-Limb Deadlift.

Hinge at the hips and slowly lower your torso until it is parallel with the floor.

Hip Hike.

Stand on a step stool with one leg. While balancing slowly drop the opposite down and back up

Mobility

The second exercise category to consider for running injury prevention is in regards to mobility. Many people mistake flexibility for mobility, but these two concepts are vastly different. Flexibility most notably refers to muscle tissue extensibility while mobility refers to a joints ability to move freely. Running is not a sport that requires a lot of muscle flexibility, but it does require good joint mobility in the ankle and hip. Dorsiflexion (toes to nose) is an important motion for the ankle. If a runner lacks proper dorsiflexion they will improperly load during initial contact of the running phase. The second important joint to work on is hip extension. If a runner lacks hip extension they will compensate for that motion by extending more in their lumbar spine, which can lead to low back pain.

Soleus Stretch

In a staggered stance stretch the lower part of the back leg by bending the knee. A stretch should be felt near the achilles tendon.

Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch.

In a ½ kneel position, tilt your hips under you while keeping an upright trunk. To increase the stretch you can shift your weight forward.

Skill

Running skill involves cadence and foot placement at initial contact. At one point many runners were being told forefoot striking was better for injury prevention. Where runners land on their foot (heel vs. forefoot) at initial contact is not a predictor of future injury; however, where they land in relation to their body’s center of mass is important. Runners with a long stride have the tendency to make initial foot-ground contact in front of their center of mass which requires more energy demand. Energy is needed for adequate engagement of the hamstring muscles to decelerate the leg advancing forward. Also, longer strides leads to more vertical displacement/bounce when running. This in turn results in greater impact at foot-ground contact and requires more energy for force absorption.

So how do runners change their cadence and foot placement at initial contact? The safest way to enhance running skills is to visit a movement expert and ask for a running analysis. Northern Edge Physical Therapy can provide runners with a comprehensive running analysis utilizing high speed cameras and force-plate instrumented treadmills to analyze gait. This assists highly trained movement experts to help identify biomechanical faults associated with running.

However, a self analysis is quite easy. First start out by identifying steps per minute when running. If possible, record a video in order to count cadence and observe any biomechanical faults. If the range is <150-170 steps per minute, work may be needed to increase the step rate. If steps per minute are over 200 steps per minute, the step rate may need to be slowed. Between 170-200 steps per minute, try increasing or decreasing cadence in order to achieve proper running mechanics. The key is to not increase running cadence by more than 10% in a training week. For example, if you run at 155 steps per minute, only increase your cadence by 5 steps at a time to assess for a change in symptoms. If your symptoms resolve, there is no need to change the cadence anymore. If symptoms persist, you can increase the cadence by 5 more steps, but not more than 10% of your original step rate. A good way to measure step rate is by using a metronome, which is free with a quick search on the internet.

Bottom line, running shoes are not as big of a concern when it comes to addressing pain associated with running. This does not mean run in the same pair of shoes forever, but once the body starts to feel the current shoes are no longer providing adequate support or cushion, it is probably time to buy a new pair. The flashier the shoes, the better!

0 Comments